Project

Umoja – Phase 1

Report by:

Nana Adwoa Adowaa Nsiah

September 5, 2025

Citation

Quansah, S., Nsiah, N. A. A., Yeboah, V. A., Asante, V., Abbey, K. D., Donkor, D. A. (2023)

Culturally Responsive STEAM Education: Enhancing the STEAM Learning Experience of African K-12 Learners by Integrating Arts and Culture

Abstract

Background

A culturally responsive STEAM module was implemented in Cape Coast, Ghana, engaging 62 African K–12 learners from 34 communities. Designed to highlight the roles of Arts and Culture in STEAM, the curriculum offered a holistic, practical, and empowering learning experience.

Objective

The learning experience sought to (1) instill creative confidence and computational thinking, (2) embed local culture, context, and symbolism in STEAM learning, and (3) empower learners to design SDG-aligned technology solutions.

Methods

Delivered over 22 hybrid sessions (27.5 contact hours), the module was framed in constructionism aligned with Resnick’s creative learning spiral, and a Culturally Responsive Learning Design (CRLD) aligned with Gay’s, and Ladson-Billings’ pedagogies on cultural relevance. Delivery included in-person makerspace workshops featuring crafts and electronics, virtual live coding, and asynchronous supports (Flip, Google Chat, tutorials).

Results

71.1% of learners reported confidence growth in creativity and innovation. Learners demonstrated strengthened identity, creative confidence, and practical STEAM literacy. They linked cultural expression to SDGs, integrated arts as advocacy, and practiced collaboration through shared prototyping and reflections.

Conclusion

This hybrid learner-centred module demonstrated the potentials of intentional Arts-integrated-Culturally Responsive Learning Design in transforming identity into capability. By merging art, culture, and computer science within SDG aligned projects, learners were positioned to innovate, articulate learnings and reflections, and appreciate the relevance of holistic STEAM learning experiences in shaping their life-long education journey.

1.0 Introduction

STEAM education cultivates problem-solving, collaboration, and creativity, skills essential for thriving in the 21st-century workforce. Yet, many digital tools designed in Western contexts risk marginalizing African learners who struggle to connect them to local realities. To bridge this gap, we developed a Culturally Responsive Learning Design (CRLD) framework, a guiding feature of algopeers.com, that reconnects learning to identity, language, local symbolism, and lived experiences of participants.

Phase 1 of the Umoja Module exemplified CRLD in action. From the very first session, learners were positioned as STEAM Advocates, invited to view arts and culture as engines of innovation rather than decorative add-ons. Early in the module, facilitators debunked the “left-brain vs. right-brain” myth to prime learners with an open mindset, emphasizing that creativity and logic are intertwined capacities leveraged across STEAM tasks (Verywell Mind, 2022; Nielsen et al., 2013). This framing legitimized bringing Afrobeat, Adinkra, storytelling, and local challenges directly into technical work, embedding cultural identity at the heart of innovation.

Within this framing, the “A” in STEAM was not treated as a narrow focus on art but as a multidimensional driver of learning. It represented aesthetics, where design sensibilities emerged in pixel-art creations and Afrobeat dance staging; agency, where learners exercised choice and authorship in shaping project directions; advocacy, where they created Flip videos on project reflections and PSAs to engage civic issues; and authenticity, where cultural elements such as Adinkra symbols, national flags, and local challenges became datasets for coding and AI training.

Projects such as the Afrobeat Pedometer, Movement Data Logger, Pixel-Art PSA Cubes, Machine Learning with Teachable Machine (Adinkra/flag datasets), and Media Arts with Flip exemplified this approach. Together, these efforts grounded technical fluency in cultural relevance, affirming the transformative potential of African identity as central to technological innovation.

2.0 Method

2.1 Participants

62 learners (ages 6–15; 51.6% female, 48.4% male) from 34 Cape Coast communities.

All learners completed the same projects, with age-appropriate scaffolds: block-based coding for 6–9 years, Python for 10–15 years.

2.2 Mode of Delivery

- In-person workshops (Saturdays, 1.5 hrs): Makerspace sessions (micro:bit and AI prototyping, Afrobeat dance as data, crafts).

- Virtual (Fridays, 1 hr): Live coding, introduction to concepts, brainstorming.

- Asynchronous: Flip video reflections, slides, video tutorials, Google Chat.

2.3 Pedagogical Frame and Alignment

- Constructionism (Papert, 1980)

- Resnick’s (2017) Projects ,Passion, Peers, Play

- CRLD (Gay, 2010; Ladson-Billings, 1995)

- Yakman’s (2008) integrated STEAM framework

3.0 Results

3.1 Learning Outcomes

Learners demonstrated:

- Creative confidence and self-identity as STEAM Advocates.

- Technical fluency in coding, sensors, design, and AI basics.

- Artistic and Cultural expression through dance, art and content creation.

- Linked classroom projects to real-world relevance via SDG framing.

- Collaboration and peer learning through critiques and shared builds.

3.2 Notable Projects

Afrobeat Pedometer (SDG 3): Learners combined Afrobeat dance with micro:bit step-counting to design a culturally engaging fitness tool. By linking familiar movement patterns to physical computing, the pedometer reframed health and exercise as joyful, culturally resonant practices rather than abstract requirements. This project deepened learners’ understanding of sensors, loops, and data display while rooting technology in local music and dance moves.

Movement Data Logger (SDG 4): This project introduced learners to data literacy by using sensors to capture and record motion. Beyond technical practice with input/output and storage, the logger helped learners visualize the link between their physical environment and data representation. By tracking everyday activities, they began to see data as both a scientific tool and an everyday storytelling tool.

Pixel-Art PSA Cubes (SDG 12): Using micro:bits and craft materials, learners designed pixel-art cubes that carried pictorial public service messages about the Sustainable Development Goals rooted to local needs. This project fused visual design with coding logic, showing how art can be a vehicle for advocacy. The cubes served as interactive sculptures (both technical artifacts and cultural expressions) that promoted community awareness around SDGs.

Marfo, 10 and Kesewaa, 12, proudly displaying their Pixel-Arts PSA cube for SDG 2 awareness.png

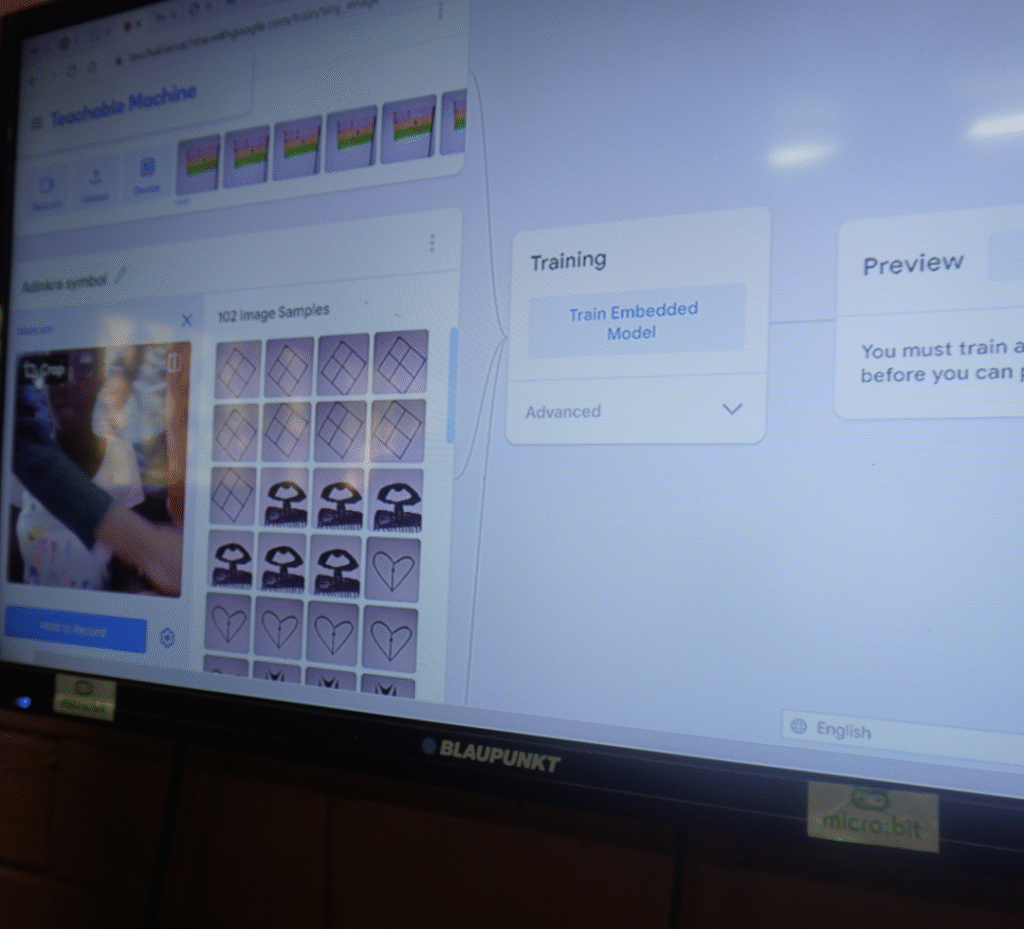

Machine Learning with Teachable Machine (SDG 9/11): Learners created datasets from Adinkra symbols and Ghanaian flags, training Teachable Machine to recognize and classify them. This activity transformed traditional art into AI-ready data, demonstrating how culture itself can be encoded and reimagined through technology. While connectivity challenges posed barriers, learners’ perseverance highlighted their resilience and creativity in adapting global AI tools to local symbols and meanings.

10-year-old N’adom Training Teachable Machine with Adinkra symbols and the Ghana

Media Arts on Flip (SDG 4/10): Microsoft Flip was used as a platform for learners to document and share their projects, reflections, and creative journeys. Videos captured not only technical demonstrations but also personal narratives, giving learners a sense of audience beyond the classroom. These digital creations amplified their voices, turning project-making into both self-expression and peer advocacy, with saved videos serving as an archive of their growth.

4.0 Discussion

4.1 Identity as Pedagogical Bedrock

The foundation of Phase 1 was laid in Session 1, where learners were positioned as STEAM Advocates and encouraged to view arts and culture not as decorative add-ons but as engines of innovation. By debunking the popular “left-brain vs. right-brain” myth, facilitators created an environment where creativity and logic were seen as complementary capacities across all STEAM work. This framing gave learners permission to bring Afrobeat, Adinkra symbols, national flags, and storytelling into their technical practice.

As the module progressed, this early identity framing became the throughline of every project. In the Afrobeat Pedometer, dance was transformed into computational data; in the Pixel-Art PSA Cubes, design sensibilities communicated sustainability; and in AI training, Adinkra symbols became datasets. Parents and learners alike recognized this cultural grounding as transformative: shy children grew expressive, while others explicitly stated pride in “using Adinkra symbols to code.” Identity, therefore, was not an afterthought but the pedagogical bedrock on which technical fluency and creative confidence were built.

4.2 Bridging Culture, Technology, and Action

The emphasis on identity naturally extended into the way learners combined cultural practices with technical tools. Arts and culture were legitimized as valid sources of data, design, and problem-solving. Projects such as the Afrobeat Pedometer and Pixel-Art PSA Cubes exemplify this fusion. Afrobeat rhythms became inputs for coding, showing that computational data could emerge from familiar cultural practices. Pixel-art, a form of creative expression, became a medium for advocacy, transforming sustainability concerns into visual public service announcements. By connecting STEM concepts to music, design, and symbolism, learners experienced technology not as abstract or imported but as joyful, relevant, and culturally situated. This affirms Yakman’s (2008) argument that the arts provide meaningful context for STEM disciplines.

4.3 From Expression to Agency

The framing of learners as STEAM Advocates also meant their cultural expressions were never limited to aesthetic outputs but were channeled into civic voice. Flip videos, PSAs, and reflective storytelling invited learners to articulate not just what they created but why it mattered. In Bruner’s (1960) terms, storytelling became a vehicle for meaning-making, transforming learners from makers of artifacts into advocates for community well-being. A learner dancing Afrobeat for health, another coding pixel-art on waste, and yet another training Adinkra datasets for AI were all practicing advocacy, still using their projects to voice concerns on health, sustainability, and cultural pride. Expression became agency, positioning learners as active contributors to civic dialogue.

4.4 Critical & Creative Thinking

The myth debunked in Session 1, that one had to either be logical or creative, was continuously countered through practice. Projects were designed so that technical fluency was interwoven with creative decision-making. For example learners chose Afrobeat as the movement pattern, demonstrating that choreography and coding could coexist as equally valid forms of knowledge, this enriched the session with a joyful and meaningful approach. Similarly, the Pixel-Art Cubes combined algorithmic logic with visual design, and the Machine Learning project transformed cultural symbols into datasets, requiring both aesthetic appreciation and careful analysis. In each case, learners enacted an integrated model of cognition, where creativity and criticality were not opposing forces but mutually reinforcing. This strengthened their problem-solving and highlighted that innovation, when rooted in culture, can be both imaginative and systematic.

4.5 Arts and Design Literacy

A distinctive feature of Phase 1 was the intentional introduction of the elements and principles of design before learners began their pixel art projects. This grounding gave them a vocabulary and framework for understanding aesthetics not as random decoration but as purposeful design. Learners explored color, balance, proportion, and rhythm, then translated these ideas into pixel art and advocacy cubes. Importantly, they were also encouraged to move beyond rules and freely express themselves, experimenting with patterns, contrasts, and symbolism drawn from their cultural environment. This dual approach structured literacy and open-ended expression which deepened their ability to see art and design as integral to technology-making. Rather than separating coding from creativity, learners recognized that design choices shaped how technology communicated, persuaded, and inspired.

5. Feedback and Reflections

- 71.1% of learners reported confidence growth in creativity and innovation.

- Parents noted transformations such as Anngrace’s mom who noticed that her daughter had evolved from being shy to becoming expressive.

Picture of 10-year-old Anngrace

- Learners valued cultural integration: 6-year-old Serwaa shared that “Using Adinkra symbols made me proud.” during her AI/ML sessions.

Picture of 6-year-old Serwaa

6.0 Challenges Faced

- Internet Limitations for AI Sessions: Connectivity challenges disrupted sessions involving tools like Teachable Machine and Glitch AI, which require stable internet access. Sessions often ran longer than planned, testing both learners’ patience and facilitators’ schedules. However, learners demonstrated perseverance by waiting extra hours, and parents showed understanding, ensuring projects could be completed despite the digital divide.

- Resource Scarcity and Prototype Scope: STEAM-focused supply shops and craft stores with essential materials are scarce in Cape Coast, limiting the range and polish of prototypes. Recycling and the creative use of locally available materials became a necessity, shaping how learners approached problem-solving and highlighting the importance of contextual innovation.

7.0 Conclusion

Phase 1 of Umoja demonstrated that culturally responsive STEAM can serve as an identity bedrock. By linking projects to learners’ culture, stories, and SDG-aligned challenges, the module moved beyond classroom discussion into practical, action-oriented outcomes. Learners gained confidence as innovators, storytellers, and problem solvers embodying the vision of STEAM not only as multidisciplinary but as culturally situated and socially impactful.

8.0 Learning Module Contributors

- Sam Quansah – Principal Investigator & Curriculum Developer

- Nana Adwoa Adowaa Nsiah – Lead Facilitator, Learning Experience & Instructional Designer

- Daniella Kristeena Abbey – Co-Learning Experience Designer

- Vera Yeboah Aninakwah – Instructional Facilitator

- Victor Ofori Asante – Instructional Facilitator

- Daisy Afedzie Donkor – Dance Facilitator

9.0 References

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The Process of Education. Harvard University Press.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally Responsive Teaching. Teachers College Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. AERJ.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms. Basic Books.

Resnick, M. (2017). Lifelong Kindergarten. MIT Press.

UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining our futures together.

Verywell Mind. (2022). Left-brain vs. right-brain dominance (myth overview).

Yakman, G. (2008). STEAM Education Framework.

Related topics

Umoja – Phase 2

Empowering African K-12 learners to co-design local civic solutions through culturally responsive, participatory STEAM education.