Project

Umoja – Phase 2

Report by:

Nana Adwoa Adowaa Nsiah

September 5, 2025

Citation

Quansah, S., Asante, V., Yeboah, V. A., & Nsiah, N. A. A. (2023)

Children as Co-Researchers and Designers: Empowering African K-12 Learners as Problem Solvers through Culturally Responsive Participatory STEAM Design

Abstract

Background

In African contexts, STEAM education is often teacher-centered, limiting learner agency. To counter this, a module was designed to engage 62 learners (ages 6–15) from 34 Cape Coast communities as co-researchers and designers in participatory STEAM design, aligned with Freire’s dialogical pedagogy.

Objective

The module aimed to (1) empower learners to co-design SDG-aligned prototypes, (2) deepen problem-solving through culturally responsive challenges, and (3) foster agency, collaboration, and ownership through team-based innovation.

Methods

The learning design and experience drew on constructionist theory and participatory design within a culturally responsive framework, and was delivered over 30 contact hours across 12 hybrid sessions. Projects and activities were framed into a competitive challenge: Algo Leagues, which engaged learners in coding, physical computing, research, and design while fostering collaboration. The curriculum was differentiated by age (6–9 and 10–15), using simplified language and methods for younger learners while still fostering agency and other core participatory elements. Facilitation was led by experienced educators with the micro:bit and administering STEAM learning for K-12 children.

Results

Learners demonstrated enhanced agency, technical proficiency, and community-oriented innovation. Results indicated 91.1% of learners could program micro:bit with little to no assistance, 86.7% gained deeper tech understanding, and 71.1% reported increased innovation confidence. This participatory approach deepened learning outcomes, transforming learners into active innovators for African contexts.

Conclusion

The module proved that children as co-researchers and designers is not an abstract idea but a viable, impactful framework for African STEAM education. By merging cultural identity, constructionist making, and participatory design, learners were positioned as innovators and advocates addressing their own civic challenges.

1.0 Introduction

In many African contexts, STEAM education often relies on a teacher-centered, broadcast approach, positioning teachers as primary knowledge distributors and learners as passive recipients. This constrained learner agency.

Phase 2 of the Umoja Module, an innovative participatory STEAM learning experience, positioned 62 K–12 learners (aged 6–15) from 34 diverse Cape Coast communities as co-researchers and designers by enabling them co-create Algo City, a reimagined, sustainable, and data-driven Cape Coast envisioned through the learners’ eyes. Within Algo City, learners tackled pressing socio-economic challenges such as flooding and urban security through hands-on prototyping.

The curriculum was grounded in Freire’s (1970) critical pedagogy, Papert’s (1980) constructionism, and Resnick’s (2017) creative learning spiral. Building on Umoja Phase 1’s arts and cultural foundation, Phase 2 emphasized learner agency within a culturally responsive, SDG-aligned design framework.

By integrating tech in tackling problems that reflect cultural contexts and local realities, participants created impactful prototypes including smart drainage systems and AI/ML digital ID solutions. Notably, 91.1% of participants achieved independent coding proficiency.

Phase 2 of the Umoja Module also marked the start of the Do Your :Bit Challenge, a global initiative of the Micro:bit Educational Foundation to inspire problem-solving in children with the micro:bit and the UN’s Sustainable Global Goals.

This report documents the design, implementation, and transformative outcomes of Umoja – Phase 2, underscoring its significance in positioning African learners as active innovators driving future glocalized solutions.

2.0 Method

2.1 Participants

- 62 learners, 51.6% female, 48.4% male.

- Ages 6-15, divided into Saraphina (6-9) and Wakanda (10-15) tribes, with three teams each.

- Learners hailed from 34 sub-urban and rural towns in Cape Coast, enriching diversity.

2.2 Mode of Delivery

Hybrid, UDL-compliant:

- In-person (Saturdays, 1.5 hrs): Makerspace for prototyping and integration into the Algo City model.

- Virtual (Fridays, 1 hr): Peer reviews, live coding, and brainstorming via Google Meet.

- Asynchronous: Tutorials, and Google Chat forums for discussions, reflections and submission of codes.

2.2.1 Algo Leagues Competing Teams

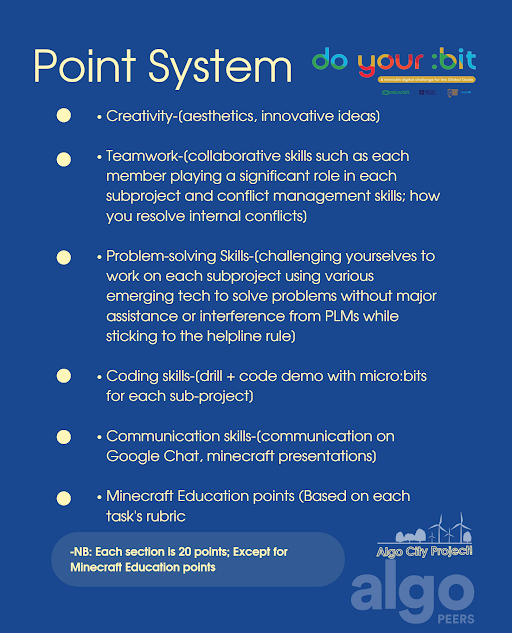

The module was framed as Algo Leagues competition with points/scoreboards for collective building and prototyping, aligned with participatory design (Brown, 2009).

Learners were organized into teams and elected team leads and assistant leads through peer voting. Each team then selected an Akan name that embodied their shared values and aspirations for the competition:

- Team Nyansawomu (Wisdom in project design): Ages 10–15

- Team Fawohodie (Freedom to explore creative solutions): Ages 10–15

- Team Nkunim (Victory and a positive attitude towards winning): Ages 10–15

- Team Pempamsie (Foresight in prototyping solutions): Ages 7–9

- Team Yɛnsesa Wiase (Literally translates to “Let’s Change the World” focusing on global impact.): Ages 7–9

- Team Adinkra Champions (Champions of Collective Cultural Values of the Adinkra symbols): Ages 7–9

3.0 Results

3.1 Learning Outcomes

- Enhanced agency and independence in innovation.

- Built advanced technical skills in micro:bit coding, AI, and sensors and prototyping.

- Fostered glocalized problem-solving through SDG-aligned prototypes.

- Promoted collaboration via team brainstorming and scoreboards.

- Demonstrated long-term impact by addressing pressing local issues.

3.2 Notable Projects

AI/ML Digital IDs of Algo City Project (SDGs 16): Learners mapped facilities, trained AI with Teachable Machine for image/sound recognition, addressing security in poor settlement planning.

Accessible Traffic Light (SDGs 3, 11): Traffic Light system for Cape-Coast Takoradi Highway, with audio-visual cues for safety and accessibility.

AquaTrench Pump (SDGs 6, 11): Dual-purpose flood control and irrigation system.

4.0 Discussion

4.1 Learner Agency in Design

Phase 2 strongly amplified learner agency by positioning children as problem-posers and solution designers rather than passive recipients of knowledge. Through student-led brainstorming, learners identified ethical responses to local challenges such as flooding, debating relocation versus infrastructure redesign, and eventually co-developing prototypes like the AquaTrench Pump. This agency aligns with Freire’s (1970) dialogical pedagogy, where knowledge is constructed through dialogue and lived realities. By choosing sub-projects and conducting peer reviews, learners acted as co-researchers shaping civic futures.

4.3 Collaborative Problem-Solving

Collaboration emerged as a cornerstone of learning. Peer reviews, leaderboards, and group prototyping fostered what Resnick (2017) describes as a “creative learning spiral” of imagining, creating, testing, and sharing. The hybrid design enabled multiple modes of participation (virtual peer accountability, in-person builds, asynchronous coding), ensuring that learners collectively advanced Algo City’s civic design. Even with limited resources, teams demonstrated resilience–iterating with recycled parts, sharing devices, and maintaining submission rates between 79–95%.

4.4 Community Ownership and Critical Thinking

Projects were not isolated technical exercises but civic interventions, strengthening a sense of ownership over Cape Coast’s challenges. Learners explicitly linked prototypes to real systems, such as comparing their Digital IDs project to Ghana’s national digital address system. This “glocal” orientation illustrates Siemens’ (2005) connectivism and the Culturo-Techno-Contextual Approach (Makinde, 2024), where learning connects local lived problems with global technological practices. Critical thinking was scaffolded developmentally: younger learners explored tangible prototypes (Piaget, 1972), while older peers engaged abstract civic reasoning and system-level debates.

4.5 Creativity and Innovation

Learners demonstrated creativity not only in coding solutions but also in material improvisation. With no 3D printers or LEGO kits, teams used cardboard, wires, and locally available scraps to prototype durable solutions. This embodied Papert’s (1980) constructionism learning by making and resonates with Nettrice Gaskins’ techno-vernacular creativity, where innovation emerges by remixing global tools with local cultural resources. Such practices position resource-constrained environments not as barriers but as catalysts for ingenuity.

5. Feedback and Reflections

- 71.1% of learners reported confidence growth in building micro:bit projects independently.

- 86.7% gained a better understanding of tech; 91.1% could program with little assistance.

- Parents noted transformations: Victoria’s mother highlighted her topping IT class; Bernadette’s father praised exposure for future potential.

- Learners felt proud designing and prototyping solutions that mattered to them and reflected their lived realities.

6.0 Challenges Faced

- Resource scarcity, leading to part recycling and lower submission rates despite full participation.

- Internet connectivity disrupting virtual coding and AI training.

- Unequal Digital Access: The project’s initial design envisioned a digital twin of Algo City using Minecraft Education, to expand opportunities for coding, gamified collaboration, and sustained project timelines. However, the tool was unavailable in the region and prohibitively expensive for our underserved communities. Although learners were excited by the potential of a gamified, collaborative environment, they had to redirect their efforts toward a tangible, hands-on version of Algo City.

7.0 Conclusion

Phase 2 of the Umoja Module illustrates that children as co-researchers and designers is not an abstract ideal. It is a viable, impactful model for African STEAM education. By combining constructionist making, creative learning principles, critical pedagogy, and culturally responsive design, the module enabled learners to move from autonomy to agency, creating solutions that were both technically sound and culturally resonant.

For STEAM in Africa, this approach offers a strategic framework that positions learners as partners in design, not just recipients of instruction by grounding learning in lived experiences and local community needs and embedding iterative creation and peer exchange at the heart of the process.

In doing so, participatory design becomes not only a method for improving educational outcomes, but also a means of empowering the next generation to be innovators, advocates, and custodians of their own futures.

8.0 Learning Module Contributors

Sam Quansah – Principal Investigator & Curriculum Developer

Nana Adwoa Nsiah – Lead Facilitator and Instructional Designer

Victor Ofori Asante – Instructional Facilitator

Vera Yeboah Aninakwah – Instructional Facilitator

9.0 References

Bers, M. U. (2018). Coding as a Playground: Programming and Computational Thinking in the Early Childhood Classroom. Routledge.

Brown, T. (2009). Change by Design: How Design Thinking Creates New Alternatives. Harvard Business Press.

Ejiwale, O. (2023). Proposing African-Centered Education in STEM for African American STEM Learners. NSBE Journal.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

Iloh, E. C. (2024). A Review: The Impact of Micro: Bit-Assisted STEM Education. ThaiJO.

Kumi, I. (2022). Teaching and Learning Paulo Freire: South Africa’s Communities of Struggle. UNISA Press.

Makinde, O. N. (2024). Breaking Barriers to Meaningful Learning in STEM Subjects in Africa. MDPI Sustainability.

Mpofu, V., & Nicolaides, A. (2019). Ubuntu: A philosophy for fostering ethical leadership in South African higher education. International Journal of Leadership in Education.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. Basic Books.

Resnick, M. (2017). Lifelong Kindergarten: Cultivating Creativity through Projects, Passion, Peers, and Play. MIT Press.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning.

Van der Vyver, C. P. (2024). Rethinking Paulo Freire’s Critical Pedagogy: Challenges and Relevance in South Africa’s TVET Sector. Academia.edu.

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Data Report: https://lookerstudio.google.com/reporting/f6d3b18e-79fe-47d1-acc1-ad5f3614263e/page/p_muykti7i0c

Related topics

Umoja – Phase 1

Enriching STEAM education through culturally responsive learning, empowering African K-12 learners to innovate with identity, creativity, and advocacy.